Possible remains of our future

Galerie Ceysson & Bénétière, NYC, USA

10 November – 12 December 2021

We sometimes like to imagine how our environment and the artifacts thereof may possibly appear in the distant future. We live in times that are the product of natural human error, but which may enter a near future where AI-provoked catastrophes could change the landscape with which we are so familiar.

Millions of years from now, advanced humans—or perhaps visiting aliens—may dig up the remnants of today’s civilizations. What will they find, and how will they interpret our relationship to the creatures around us, or our relationship to art?

Sabatté’s work begins with an analogy between nature and almost primitive artifacts. The trajectory of his work questions the age of Anthropocene—not so much how we mirror nature, but how nature mirrors us back. His work therefore operates on a different plane, a different spatiotemporal axis, where the cyclical processes are longer, where time works differently, and where everyday events are replaced by emphasis on the deeper ontological framework. The artist characterizes his approach in one of the interviews: “I’m doing what nature does better than me. I am organizing the symbols, not applying them or directly using them, and defending my uselessness in the face of a hyper-productive world.”

His first solo exhibition at Ceysson Bénétière gallery, I will allow myself to say, is a less narrativized version of his museum solo show at the Museum of contemporary art St Etienne that started in September.

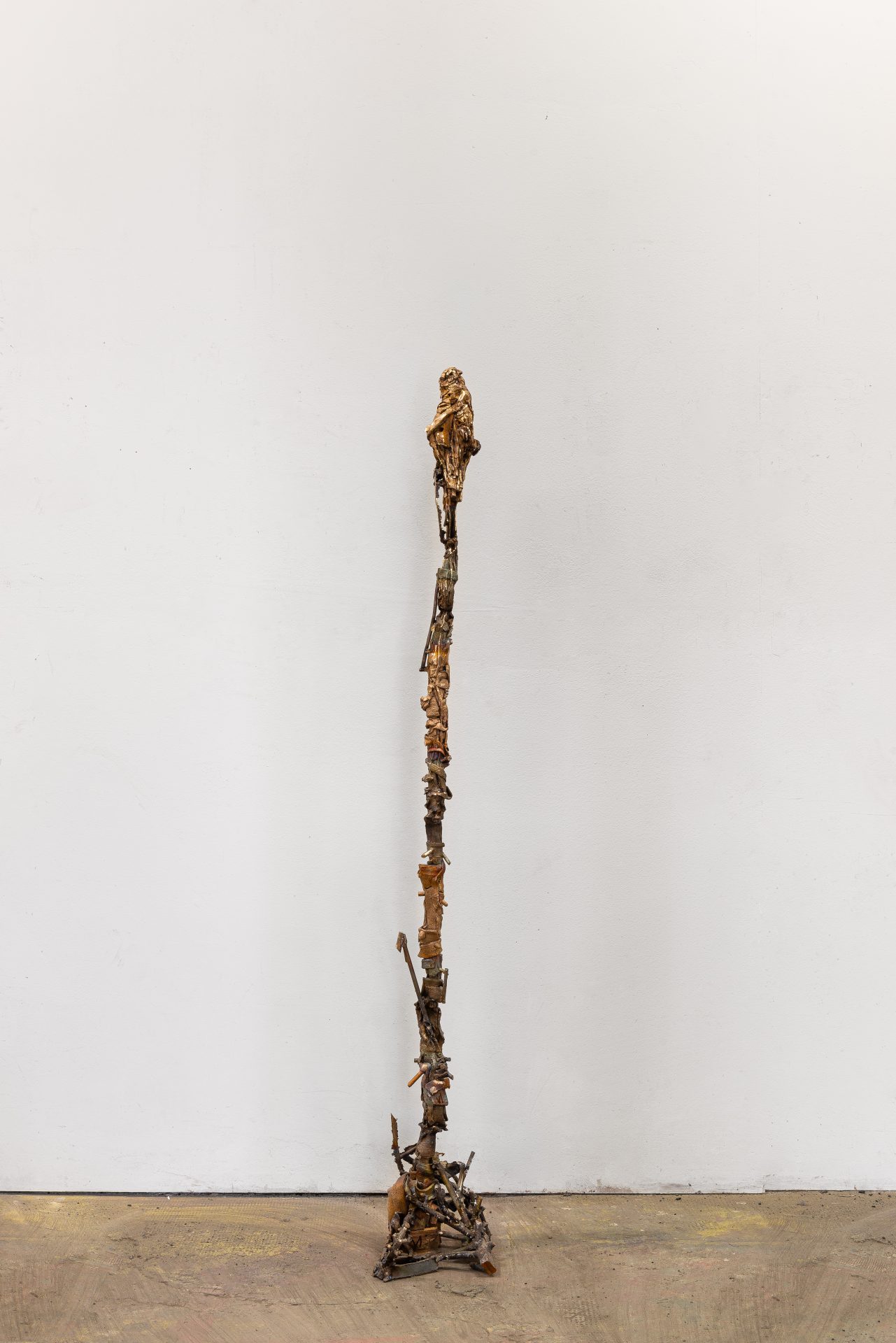

Sculptures that we see in the gallery ask the question—what do we leave behind? It is whatever is buried in the ground. They are made of a specific mix of diverse materials that look like a ground but are composed from concrete, pigments and natural fibers. Giving the impression to be immobile and incredibly silent. Their shapes are not easily defined and deliberately left to the viewer to construct their own narrative. His more abstract work is sourced from different visual languages using an alchemical approach towards the material as a warning sign for the ambivalent relationship that we cultivate today with our environment.

New works reflect different ways of dealing with nature and our destructive behavior towards it. Consider his fairy creatures made from nail clippings or wolves made of dust. Isn’t the fairy, paradoxically, the ultimate pre-human and post-human subject all at once? Thus, in his use of leftover materials (nails, skin, dust, etc.) we encounter Sabatté’s radically connected worldview—an alternative understanding of nature which challenges the various presumptions of occidental thought (its dualistic nature, etc.) and channels the rediscovered knowledge of Amerindian metaphysics (animism, totemism, shamanism, etc.), for which this novel understanding is, of course, nothing new.

Nevertheless, the true source is his childhood memories originated from the Grotte de Merveilles (Cave of Wonders) in Pyrenees. The way the ancients created images is a recurring inspiration in the work. They would use their hands as stencils, placing their hand right up against the rock surface and then blowing pigment through the long bones of the animal onto the hand and surrounding rock surface, leaving a negative impression of the hand. This is the same technique used to make some of the images. These are the origins of the visual dictionary that the artist has cultivated during his creative process by establishing unexpected relationships between materials, pigments and images.

Sabatté’s work is therefore spectral, almost hauntological in its various configurations, as it is a materialization of everything our modern subjectivities fail to (but simply must) see.

Lara Pan, June 2021

With the support of Centre national des arts plastiques (National Centre for Visual Arts), France